Understanding Property Deeds in Real Estate

Learn how property deeds work, what they contain, and which type of deed best protects your ownership rights.

Property Deeds Explained: A Practical Guide for Home Buyers and Owners

When real estate changes hands, the property deed is the core document that makes the transfer legally effective. A deed spells out who is giving up ownership, who is receiving it, and what rights in the property are being conveyed. Without a valid deed, you cannot reliably prove you own a home or parcel of land.

This guide walks through what a deed is, how it differs from title, what must appear in the document, and how major types of deeds affect your level of protection as a buyer or recipient of property.

Deed vs. Title: Two Related but Different Concepts

People often use the words deed and title interchangeably, but in real estate law they refer to different things.

- Deed: A written, signed legal instrument used to transfer ownership interests in real property from one party to another.

- Title: The legal concept of ownership itself – the collection of rights to possess, use, control, and dispose of the property.

In everyday terms, the deed is the paper used to move title from one person to another. Title itself is an invisible bundle of rights, but the deed is the evidence that those rights were transferred.

Essential Legal Elements of a Valid Deed

State property laws set specific requirements that a deed must satisfy to be legally effective. While the details vary by jurisdiction, several core elements appear across U.S. law.

- Competent grantor – The person transferring the property (grantor) must have legal capacity and the right to convey the interest.

- Identifiable grantee – The person or entity receiving the property (grantee) must be named with reasonable certainty.

- Words of conveyance – Language clearly indicating an intention to transfer an interest in real estate (for example, words similar to “grants,” “conveys,” or “quitclaims”).

- Legal description of the property – A precise description that uniquely identifies the real estate, often using a lot and block description, metes-and-bounds, or a reference to a recorded plat.

- Grantor’s signature – The deed must be signed by the grantor; some states also require the grantee’s acceptance.

- Delivery and acceptance – The deed must be delivered by the grantor and accepted by the grantee to complete the transfer.

- Compliance with state formalities – These may include notarization, witness signatures, or specific statutory language.

Most states also require that a deed be recorded in the local land records office to protect the grantee against competing claims, although the transfer between the parties usually occurs upon delivery and acceptance.

Key Players Named in a Property Deed

Every deed identifies the parties involved in the transfer. Understanding these roles will help you read and interpret the document:

- Grantor: The current owner (individual, couple, business, estate, or trust) who is conveying their interest in the property.

- Grantee: The recipient of the property interest, such as a buyer, heir, spouse, or trust beneficiary.

- Trustee (in some deeds): A neutral party who holds title for the benefit of others under a trust or deed of trust framework.

- Lender or beneficiary (for secured transactions): The party that holds the security interest when the property is used as collateral, such as under a mortgage deed or deed of trust.

What Information Typically Appears in a Deed?

Beyond the basic legal elements, you will usually see several additional components in a modern real estate deed:

- Date of the deed – When the grantor executed the document.

- Consideration clause – A statement of what the grantee is giving in exchange, often the purchase price or a symbolic amount (such as “for ten dollars and other valuable consideration”).

- Type of deed – Identification as a general warranty deed, special warranty deed, quitclaim deed, or other recognized form.

- Habendum clause – Language describing the extent and duration of the estate being conveyed (for example, a fee simple interest, life estate, or a specific share of co-ownership).

- Reservations or exceptions – Any rights the grantor is keeping or limiting, such as mineral rights, easements, or use restrictions.

- Signature block and acknowledgment – The grantor’s signature, followed by a notary acknowledgment as required by state law.

- Recording information – When filed with the county or local recorder, the deed receives a recording stamp and reference details.

Major Categories of Property Deeds

From the buyer’s standpoint, the most important distinction among deeds is the level of warranty or protection the grantor provides regarding the quality of title. Public land-grant and property law sources typically group modern deeds into a few broad categories.

| Deed Category | Typical Protection for Grantee | Common Uses |

|---|---|---|

| General warranty deed | Highest; grantor warrants clear title against all claims, both before and during their ownership. | Most conventional home sales and mortgage-financed purchases. |

| Special (limited) warranty deed | Moderate; grantor only warrants against title defects arising during their period of ownership. | Commercial properties, bank-owned real estate, some estate or trust transfers. |

| Quitclaim deed | Lowest; no warranties. Grantor conveys whatever interest they may have, if any. | Transfers between family members, divorce-related conveyances, clearing up title defects. |

Common Types of Deeds and How They Work

1. General Warranty Deed

A general warranty deed provides the broadest protection for buyers. The grantor promises that:

- They hold good title to the property.

- The property is free from undisclosed liens, encumbrances, and adverse claims, no matter when they arose.

- They will defend the grantee against lawful claims by others.

This deed is widely used in residential transactions involving mortgage financing because it offers lenders and buyers the highest level of assurance.

2. Special or Limited Warranty Deed

A special warranty deed (sometimes called a limited warranty deed) narrows the scope of protection. The grantor only warrants that:

- No title defects or encumbrances were created during their own period of ownership.

- They have not previously conveyed the property to someone else.

Any problems that predate the grantor’s ownership are outside the warranty. This form is common in commercial sales and in transactions where the seller has not occupied the property, such as some corporate or estate-owned real estate.

3. Quitclaim Deed

A quitclaim deed conveys whatever interest the grantor may have, if any, but makes no promises about the state of title. If the grantor holds nothing, the grantee receives nothing. For that reason, quitclaim deeds are typically used only where:

- The parties have a preexisting relationship and a high degree of trust (spouses or close family).

- One co-owner is removing themselves from title, such as in a divorce or refinancing.

- A minor defect in the record needs to be corrected, like resolving a misspelling in a prior deed.

Because there are no warranties, buyers who pay market value rarely accept a quitclaim deed without additional protections like title insurance and thorough title searches.

4. Grant Deed

A grant deed is recognized in some states and functions as a middle-ground warranty form. The grantor typically promises that:

- They have not previously conveyed the property to another person.

- There are no undisclosed encumbrances that arose during their ownership.

However, a grant deed usually does not cover title defects arising before the grantor acquired the property, so its scope can resemble that of a special warranty deed.

5. Deeds Involving Security Interests: Mortgage Deeds and Deeds of Trust

In transactions where real property secures a loan, the deed may have a dual function: documenting ownership and granting a security interest to a lender.

- Mortgage deed – Used in some states to create a lien in favor of the lender. If the borrower defaults, the lender may seek a judicial foreclosure to enforce its rights.

- Deed of trust – Instead of a direct mortgage, legal title may pass to a trustee, who holds it for the benefit of the lender (beneficiary) until the loan is repaid. Many states use deeds of trust instead of traditional mortgages because they can allow for nonjudicial foreclosure procedures.

When the loan is paid off, a reconveyance deed or similar instrument is recorded to return full title to the borrower.

6. Special-Purpose Deeds

Certain circumstances call for deed forms tailored to a specific legal outcome. Examples include:

- Tax deed – Issued when a property is sold for unpaid property taxes, conveying the interest of the taxing authority to the purchaser.

- Deed in lieu of foreclosure – Used when a borrower voluntarily conveys the property to a lender to avoid foreclosure, transferring the borrower’s rights to the lender in satisfaction of the debt.

- Sheriff’s or trustee’s deed – Conveys property sold under court order or power of sale, such as at a foreclosure auction.

These deeds often provide limited or no warranties and may signal that additional diligence is necessary to evaluate title risks.

How Deeds Affect Buyer Protection and Risk

The label on the deed matters because it tells you what legal promises the grantor is making. That, in turn, shapes your exposure to future title problems.

- High protection (general warranty): You can seek compensation from the grantor if an undisclosed lien, boundary dispute, or ownership claim later surfaces that falls within the warranty period.

- Moderate protection (special warranty / grant deed): You may only have recourse for issues that arose while the grantor owned the property.

- Minimal or no protection (quitclaim or distressed-sale deeds): You bear most of the risk; your main protection comes from a thorough title search and, often, title insurance rather than from the deed’s warranties.

Regardless of deed type, many buyers obtain title insurance. Title insurance policies, often required by mortgage lenders, help protect against financial losses caused by defects in title that were unknown at the time of purchase.

Recording the Deed: Why It Matters

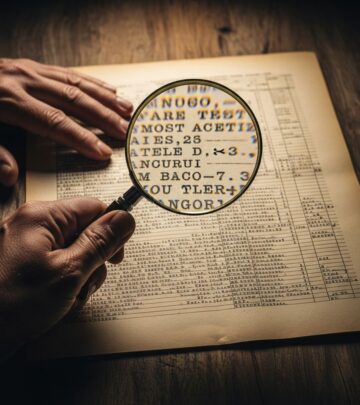

Once a deed is signed, delivered, and accepted, ownership can transfer between the parties. But to protect that ownership against third parties, the deed should be recorded in the appropriate land records office, such as a county recorder or registrar of deeds.

- Recording gives public notice of the transfer, which is critical in determining priority if competing claims arise.

- Most states follow a recording statute (race, notice, or race-notice) that favors purchasers who record promptly and in good faith.

- Unrecorded deeds may be vulnerable if the grantor improperly conveys the property again and the later buyer records first.

Buyers should confirm that the closing process includes prompt recording of the deed and that the recorded copy reflects accurate names and legal descriptions.

Practical Tips for Reading and Using Property Deeds

If you are buying or receiving real estate, you do not need to be a lawyer to spot key issues in a deed. Consider the following checklist:

- Verify that your name and the grantor’s name are spelled correctly and match your legal documents.

- Confirm the legal description matches the survey, title report, or existing public record.

- Identify the type of deed (warranty, special warranty, quitclaim, etc.) and understand the associated level of protection.

- Look for any exceptions, reservations, or easements that might affect how you can use the property.

- Ensure the deed was properly signed and notarized in accordance with state law.

- Keep copies of both the executed deed and the recorded version with the official recording information.

For complex transactions, unusual deed types, or high-value properties, consultation with a real estate attorney can help you understand how the deed interacts with other legal instruments such as mortgages, easements, covenants, and trust documents.

Frequently Asked Questions About Property Deeds

Q1: Is the name on the deed the same as the name on the mortgage?

Not always. The deed lists the legal owners of the property, while the mortgage or deed of trust lists the borrower responsible for the loan. In many cases they match, but co-signers or non-borrower spouses may appear on one document and not the other.

Q2: Do I own my house once the deed is in my name?

If a valid deed has been delivered, accepted, and recorded, you generally hold legal title. However, if there is a mortgage or deed of trust, the lender still has a security interest that could lead to foreclosure if payments are not made.

Q3: Can I transfer my home to a family member with a quitclaim deed?

Yes, quitclaim deeds are commonly used for transfers among family members or between spouses because they are simple and inexpensive. Keep in mind that the recipient receives no warranty of title, and tax or estate-planning consequences should be reviewed with professionals.

Q4: What happens if my deed is never recorded?

Between you and the grantor, the transfer may still be valid if state requirements for delivery and acceptance are met. But failing to record can expose you to serious risks if the grantor later sells the same property again or if creditors assert claims, because third parties may not be bound by an unrecorded deed under state recording statutes.

Q5: How is a deed different from a will or trust?

A deed immediately transfers a present interest in real property when delivered and accepted. A will only becomes effective at the testator’s death and must go through probate, while a trust can hold title for beneficiaries under ongoing terms. Each tool serves a different role in estate and property planning.

References

- Deeds Types — University of Maine, School of Forest Resources. 2015-05-01. https://umaine.edu/svt/wp-content/uploads/sites/105/2015/05/DeedsTypes.pdf

- Types of Deeds to Transfer Ownership of Real Property — Trust & Will. 2023-08-10. https://trustandwill.com/learn/types-of-deeds

- Types of Deeds in Real Estate — LawDistrict. 2025-01-05. https://www.lawdistrict.com/articles/types-of-deeds

- House Deed: Defined and Explained — Rocket Mortgage. 2024-03-18. https://www.rocketmortgage.com/learn/house-deed

- Different Deeds Mean Different Things — Ohio State University Extension, Farm Office. 2023-09-28. https://farmoffice.osu.edu/blog/thu-09282023-953pm/different-deeds-mean-different-things

Read full bio of Sneha Tete