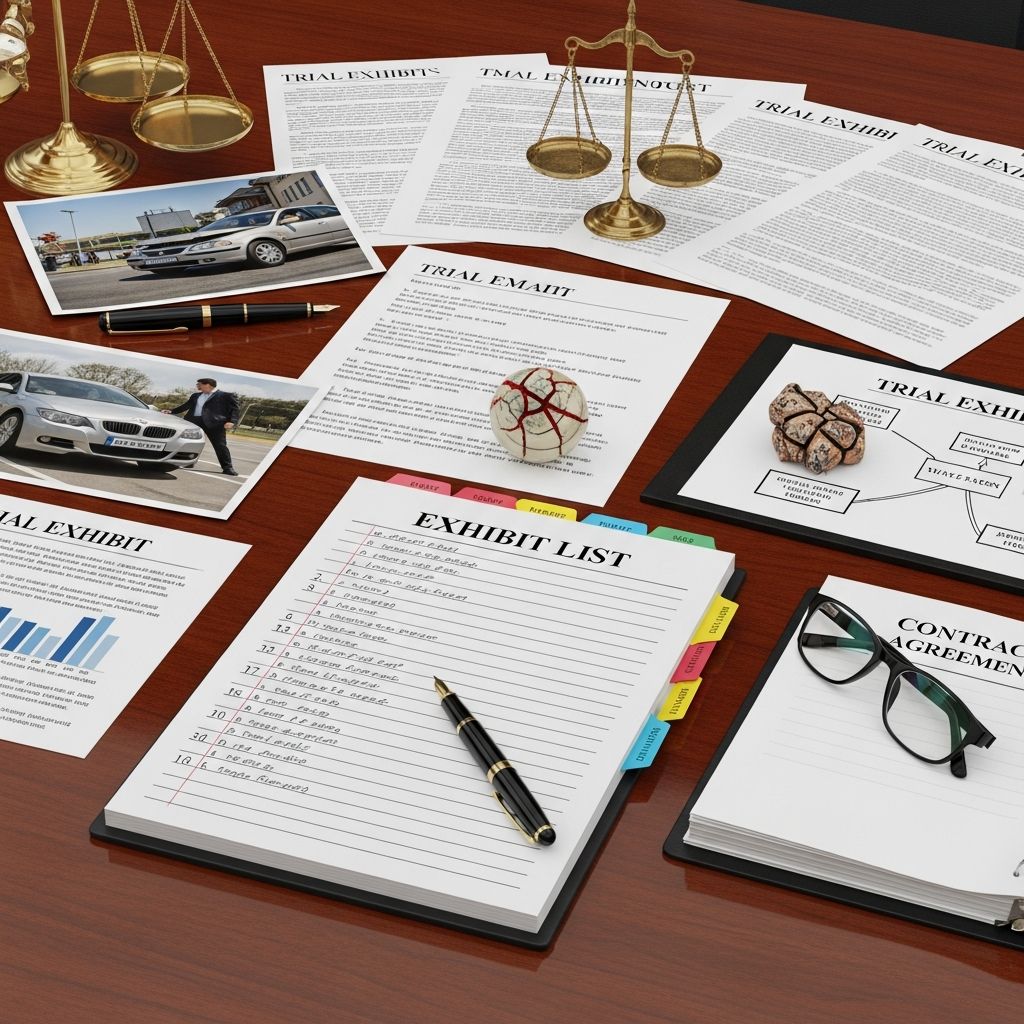

Mastering Exhibit Lists and Trial Exhibits

A practical, step-by-step guide to organizing, listing, and presenting exhibits so your evidence is clear, admissible, and persuasive at trial.

Exhibits are the backbone of any trial. Contracts, medical records, photographs, emails, and videos all become persuasive tools only when they are properly selected, organized, disclosed, and presented. A clear, complete exhibit list and well-prepared exhibits not only keep you in compliance with court rules, but also help the judge and jury understand your case with minimal friction.

This guide walks through a practical workflow for planning, building, and using your exhibit list and trial exhibits, with an emphasis on professional organization, admissibility, and modern digital practices.

Why Exhibit Planning Matters

Courts expect counsel to exchange exhibit lists and copies of proposed exhibits in advance so that evidentiary issues can be narrowed before trial and proceedings run efficiently. Poorly prepared exhibits slow the trial, frustrate the judge, and can undermine your credibility.

Effective exhibit planning supports several key goals:

- Compliance with rules of civil procedure and evidence.

- Clarity in how evidence fits the elements of each claim and defense.

- Efficiency in locating, marking, and presenting exhibits during examination.

- Persuasion by making the story of the case visually and logically accessible.

Start with the Rules: The Legal Framework

Before drafting an exhibit list, you must know the procedural and evidentiary rules that govern exhibits in your court.

Key rule sources to review

- State or federal rules of civil procedure for disclosure and pretrial exchange requirements.

- Rules of evidence for relevance, authentication, and exclusion (e.g., Rules on relevance, hearsay, and authenticity).

- Local rules and standing orders setting specific exhibit list formats, deadlines, and pre-marking requirements.

- Trial management orders that may include exhibit exchange schedules and procedures for objections.

Many courts specify the minimum information that must appear on an exhibit list and may provide a sample format. Always adapt your internal templates to those requirements.

Designing an Exhibit Tracking System

A disciplined tracking system is essential from the moment you begin identifying potential trial evidence. Think of it as a database that evolves from broad evidence collection into a refined list of trial exhibits.

Core fields for an internal exhibit index

Your internal index can contain more detail than the formal list filed with the court. Typical useful fields include:

- Exhibit identifier (temporary ID, later mapped to official number/letter)

- Offering party (plaintiff, defendant, third party)

- Short descriptive title (e.g., “Email from Smith to Jones 05/10/22”)

- Document type (contract, photo, medical record, invoice, video, demonstrative, etc.)

- Date of the document or event

- Source (e.g., subpoena, party production, expert report)

- Relevance / issues supported (liability, damages, credibility, etc.)

- Bates range or file path

- Admissibility status (likely admissible, hearsay concern, needs foundation, subject to motion in limine)

- Trial status (planned, likely used, backup only, withdrawn)

Tools for managing the index

- Spreadsheets for small to mid-size cases.

- Litigation support software for large or document-heavy matters.

- Cloud storage with structured folders mirroring your index, using consistent file naming (e.g., “PX001_Contract_2019-03-01.pdf”).

From Evidence Universe to Trial Exhibits

The set of documents produced in discovery is almost always larger than what you will use at trial. Exhibit selection is both a strategic and a practical exercise.

Step 1: Gather and review potential exhibits

- Collect all documents, communications, physical items, photographs, diagrams, and multimedia that might be used as evidence.

- Map each item to the claims, defenses, and elements it may prove or rebut.

- Identify gaps where additional records or demonstratives are needed.

Step 2: Evaluate admissibility and evidentiary issues

At this stage, filter potential exhibits based on basic admissibility principles under the applicable rules of evidence:

- Relevance: Does the exhibit tend to prove or disprove a material fact?

- Authentication: Can you show it is what you claim it is (e.g., through a witness with knowledge or a custodian of records)?

- Hearsay and exceptions: Is the document an out-of-court statement offered for its truth, and if so, does an exception apply (e.g., business records)?

- Prejudice vs. probative value: Could it be excluded if its unfair prejudice substantially outweighs its probative value?

Flag any exhibit that may require a motion in limine or a pretrial ruling on admissibility.

Step 3: Decide which exhibits to offer at trial

After screening for relevance and admissibility, refine the list based on trial strategy:

- Prioritize exhibits that will be used in opening, critical examinations, and closing.

- Retain backup exhibits that support impeachment or rebuttal.

- Eliminate duplicative items unless needed for different purposes (e.g., summary vs. original data).

Building the Official Exhibit List

Once your internal index is solid, translate it into the formal exhibit list required by your court. This document is usually exchanged pretrial and filed with the court.

Typical content of a filed exhibit list

Exact requirements vary, but a formal exhibit list commonly includes:

| Field | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Exhibit number or letter | Official identification used at trial (e.g., Exhibit 1, Exhibit A). |

| Party designation | Indicates whether it is a plaintiff’s, defendant’s, or joint exhibit. |

| Short description | Enough detail to distinguish the item without revealing privileged matter. |

| Date (if applicable) | Helps the court and opposing counsel place the exhibit chronologically. |

| Objection column | Some courts require each side to list objections (e.g., hearsay, relevance). |

| Admitted/Rejected column | Used during trial to track rulings on each exhibit. |

Numbering and labeling conventions

- Use a consistent numbering scheme for each party (e.g., plaintiff uses 1–500; defendant uses A–Z, AA–ZZ).

- Confirm whether the judge has preferred conventions in a standing order or sample form.

- Pre-mark physical exhibits with stickers that match your list (e.g., “PX-15”).

- Mirror the same identifiers in digital filenames and bookmarks.

Preparing Physical Exhibits

Even in increasingly digital courtrooms, physical binders remain common. Poorly assembled binders waste time and can cause confusion when witnesses are testifying.

Copy sets and binders

At minimum, you normally need a complete set of physical exhibits for:

- The court (judge, and sometimes the clerk)

- Opposing counsel

- Your own trial team

Some courts or practices also call for a separate set prepared for use by witnesses, particularly in bench trials or evidentiary hearings.

Binder organization tips

- Arrange exhibits in numerical or alphabetical order, consistent with the list.

- Use tab dividers with the exhibit number or letter printed clearly.

- Place a current copy of the exhibit list at the very front of each binder.

- For voluminous exhibits (e.g., medical records), use internal tabs or pagination for easy navigation.

- Include color copies where color is material (e.g., photographs or diagrams).

Preparing Digital Exhibits

Many courts now allow or require electronic presentation of exhibits, particularly in complex or remote proceedings. Effective digital preparation both satisfies court requirements and simplifies presentation.

Digital formatting best practices

- Convert documents to searchable PDF where possible.

- Apply consistent file naming: party + exhibit number + brief descriptor (e.g., “DX-A_RepairInvoice_2023-06-12.pdf”).

- Bookmark multi-page PDFs by section (e.g., “ER Records – 2019”, “Operative Report”).

- Confirm the court’s accepted file formats and size limits for electronic exhibits.

Organizing digital repositories

- Create top-level folders such as “Admitted Exhibits”, “Demonstratives”, “Deposition Designations”.

- Subdivide by offering party and exhibit sequence.

- Use the same identifiers as on the official exhibit list to avoid confusion in court.

- Test all files on the actual hardware and software you will use at trial.

Demonstrative Exhibits and Visual Aids

Demonstrative exhibits such as charts, timelines, and diagrams can make complex evidence understandable. However, courts often treat them differently from substantive exhibits because they illustrate, rather than constitute, evidence.

Planning demonstratives

- Identify complex topics (e.g., medical causation, financial calculations) that would benefit from visual explanation.

- Confirm whether the court requires pre-disclosure or pre-approval of demonstratives.

- Ensure that each demonstrative fairly reflects the underlying evidence and does not mislead.

Integrating demonstratives with the exhibit list

Some jurisdictions ask that demonstratives be listed on the exhibit list; others treat them separately. Whatever the practice:

- Use a distinct numbering or labeling scheme if required (e.g., “D-Chart 1”).

- Maintain a parallel internal index noting the foundation and source documents for each visual.

- Have printable versions available for the court and opposing counsel.

Coordinating Exhibits with Witnesses and Trial Themes

An exhibit list is not just a compliance document; it is a map of how you will tell the story of your case. Align each exhibit with witness testimony and overall trial themes.

Creating a witness–exhibit matrix

Build a matrix linking witnesses to the exhibits you plan to use with them:

- List witnesses on one axis and exhibit numbers on the other.

- Mark which exhibits each witness will authenticate or explain.

- Note the element or issue each combination addresses (e.g., “causation”, “damages”, “impeachment”).

This matrix helps ensure that foundation is properly laid and that no critical exhibit is overlooked during examination.

Sequencing exhibits for impact

- Introduce key exhibits early with foundational witnesses to anchor your theory of the case.

- Group related exhibits (e.g., a contract, subsequent amendments, and relevant correspondence) for a coherent narrative.

- Reserve some exhibits for cross-examination where they will have maximum impeachment value.

Handling Objections and Motions in Limine

Exchange of exhibit lists gives each side an opportunity to raise objections and narrow evidentiary disputes before trial. Many courts require or encourage counsel to meet and confer about objections and to file motions in limine to resolve recurring issues.

Common bases for exhibit objections

- Lack of relevance or tendency to confuse or mislead.

- Hearsay without a recognized exception.

- Lack of proper authentication or foundation.

- Privilege or work-product concerns.

- Cumulative evidence where less burdensome proof is available.

Practical tips

- Use your exhibit index’s “admissibility” and “objection” columns to track issues.

- Prepare brief, rule-based explanations for each objection or response.

- Bring clean, highlighted copies of key rules of evidence to the pretrial conference and trial.

Day-of-Trial Procedures for Exhibits

By the time trial begins, your exhibits should be ready for immediate use. Last-minute scrambling to mark or copy exhibits reflects poorly on counsel and slows the proceedings.

Courtroom logistics checklist

- Verify that the court has the final exhibit list and working copies of all exhibits.

- Confirm the method of marking exhibits on the record (verbal identification, clerk-applied stickers, or pre-marked labels).

- Ensure your team knows which binder or digital folder holds each group of exhibits.

- Test any technology you will use (document camera, trial presentation software, video playback).

Managing exhibits during witness examination

- State the exhibit number clearly each time you refer to it.

- Ask permission to approach a witness with an exhibit when required by courtroom practice.

- Offer the exhibit into evidence explicitly after laying foundation; do not assume it is admitted just because it was shown.

- Track rulings on admission in real time on your exhibit list to avoid re-offering or misusing excluded items.

Maintaining a Clean Record for Appeal

Clear exhibit handling helps create a reliable appellate record. Ambiguous references like “that document” or “the email we just saw” can complicate appellate review.

- Use exhibit numbers when questioning witnesses and making arguments.

- Ensure each admitted exhibit is correctly labeled and preserved by the clerk.

- For digital materials, verify that the final admitted versions are provided to the court according to local protocol.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: When should I start building my exhibit list?

Start building a preliminary exhibit index as soon as you begin receiving discovery. Refine it throughout discovery and motion practice, then convert it into the formal exhibit list by the deadline in the scheduling or pretrial order.

Q: How many copies of each exhibit do I need?

At minimum, prepare a full set for the court, one for opposing counsel, and one for your own team. Some judges also prefer a separate witness set or electronic copies for use on courtroom displays.

Q: Do I need to list impeachment exhibits?

Many courts allow or require disclosure of exhibits that could be used for any purpose, including impeachment, but practices vary. Review the rules and any pretrial orders carefully, and when in doubt, err on the side of disclosure unless doing so would reveal privileged strategy.

Q: How are digital exhibits handled differently from paper exhibits?

Digital exhibits must comply with court specifications on file type, naming conventions, and size limits, and often must be pre-uploaded to a court system or exchanged on approved media. You should also ensure that bookmarks, page numbering, and on-screen displays align with your official exhibit numbers.

Q: What happens if an exhibit on my list is never offered at trial?

Listing an exhibit does not obligate you to offer it; it simply preserves your ability to use it. If circumstances change, you may choose not to use certain listed exhibits, and the court’s admitted-exhibit log will reflect only those actually received into evidence.

References

- Drafting and Exchanging Exhibit Lists for a Federal Civil Trial — Dechert LLP. 2022-06-01. https://www.dechert.com/content/dam/dechert%20files/people/LIT_Summer22_SpotlightOn.pdf

- Exhibit List for Trial: Organizing Evidence — U.S. Legal Support. 2023-08-15. https://www.uslegalsupport.com/blog/exhibit-list-for-trial/

- How to Introduce and Present Exhibits at Trial — U.S. Legal Support. 2023-08-22. https://www.uslegalsupport.com/blog/how-to-prepare-exhibits-for-court/

- Exhibit List Sample and Guidelines — U.S. District Court, Eastern District of Texas. 2017-02-14. https://www.txed.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/judgeFiles/Final_Exhibit%20List%20Sample%20and%20Guidelines%202.14.17%20JMG.pdf

- Paralegal Best Practices for Preparing Exhibits for Trial — AgileLaw. 2015-09-10. https://www.agilelaw.com/blog/preparing-exhibits-trial/

- Preparing for Trial: Witnesses & Exhibits — Superior Court of California, County of Tulare. 2024-12-20. https://www.tulare.courts.ca.gov/system/files/forms-and-filings/preparing-trial-12-20-2024.pdf

Read full bio of medha deb