Legal Consequences When Parents Give Drugs to Children

Explore how criminal law treats parents who give drugs to minors, from child endangerment charges to custody and long-term consequences.

When Parents Give Drugs to Children: Crime, Consequences, and Protection

When a parent gives illegal drugs or misuses prescription medication with a child, the law treats it as a serious crime and a form of child abuse or endangerment. This conduct can trigger criminal prosecution, loss of custody, and long-term legal consequences that affect both the parent and the child.

This article explains how U.S. law typically addresses situations where a parent supplies, shares, or exposes a child to drugs, what penalties may apply, and what options exist for families facing these accusations.

1. Why Giving Drugs to Kids Is Treated So Harshly

Children and teenagers are more vulnerable than adults to the physical, psychological, and social harms caused by alcohol and other drugs. Their brains are still developing, and early substance use is strongly linked to higher rates of addiction, mental health problems, accidental injury, and death. These risks underpin why lawmakers impose harsh penalties when adults—and especially parents—introduce children to drugs.

From a legal perspective, the parent–child relationship makes the conduct more serious because the law expects parents to protect, not endanger, their children. Many states therefore treat drug-related crimes more severely when the victim is a minor or when the conduct occurs in the child’s home or presence.

2. Core Crimes Involved When Parents Give Drugs to Minors

Depending on the facts and the state, a single incident can lead to several overlapping charges. While the labels and statutes vary, the following categories are common:

2.1. Child Endangerment and Child Abuse

Most states have laws criminalizing conduct that places a child at substantial risk of physical or emotional harm, even if the child is not actually injured. Giving a child drugs, allowing them to use drugs, or using drugs in a way that exposes the child to serious danger may qualify as child endangerment or child abuse.

- Endangerment by exposure: Allowing a child to see, smell, or have access to illegal drugs or drug paraphernalia can be its own crime in some states, even without ingestion.

- Endangerment by ingestion: Knowingly allowing or encouraging a child to ingest or inhale a controlled substance is frequently treated as a felony.

- Enhanced penalties when harm occurs: If the child is injured or dies as a result of exposure or ingestion, the offense level and possible sentence increase substantially.

2.2. Drug Distribution, Delivery, or Furnishing to a Minor

Drug laws often distinguish between simple possession and supplying drugs to someone else. When the recipient is a minor, many statutes add special enhancement provisions.

- Distribution to a minor: Giving, sharing, selling, or otherwise transferring a controlled substance to a child can be charged as distribution or furnishing to a minor, frequently a felony with elevated penalties compared with adult-to-adult distribution.

- Location-based enhancements: Some states impose additional penalties when the drugs are provided in certain locations (such as near schools or playgrounds), or when the adult occupies a position of trust or authority over the child, as a parent or caregiver.

2.3. Misuse of Prescription Medication

Even when a drug is legally prescribed to the parent, it is often illegal to share it with others, especially a child. Misusing prescription opioids, sedatives, or stimulants with children can lead to charges for:

- Unlawful delivery of a controlled substance.

- Child endangerment or abuse based on unsafe administration of medication.

- Neglect if the parent’s own impairment interferes with safe caregiving.

Some states provide limited exceptions for medications given according to a valid pediatric prescription, but those protections usually do not apply when the parent intentionally offers their own prescriptions for non-medical use.

2.4. Neglect Related to Substance Use

Even if the parent does not directly hand drugs to the child, their substance use may still be considered neglect or abuse when it compromises the child’s basic needs or safety. For example, child welfare agencies often treat chronic parental substance misuse as neglect when it leads to inadequate supervision, unsafe living conditions, or untreated medical issues.

| Legal Theory | Typical Conduct | Common Charge Level (Varies by State) |

|---|---|---|

| Child Endangerment/Abuse | Letting a child access or use drugs; using drugs around a child | Misdemeanor to felony; higher if injury or death occurs |

| Distribution to a Minor | Giving or selling drugs directly to a child | Felony, often with enhanced penalties |

| Prescription Misuse | Sharing prescribed opioids or sedatives with a child | Felony or serious misdemeanor, plus licensing issues for medical professionals |

| Neglect | Substance use that prevents adequate care or supervision | Grounds for dependency case; can also be a crime in some states |

3. How Harm to the Child Affects Charges and Sentencing

In many jurisdictions, the severity of the outcome for the child directly influences the level of the offense and the potential sentence.

- No injury but serious risk: Often charged as a lower-level felony or high-level misdemeanor (e.g., child endangerment or exposure-related offense).

- Non-fatal injury: If the child suffers bodily injury, overdoses but survives, or needs medical treatment, the offense may be raised to a more serious felony level.

- Death of the child: When a child dies from drug exposure or ingestion, the parent may face charges such as felony child abuse resulting in death, drug distribution causing death, or even manslaughter or murder, depending on the facts and state law.

Judges also consider aggravating and mitigating factors at sentencing, such as previous convictions, the child’s age, evidence of addiction treatment, and the parent’s overall caregiving history.

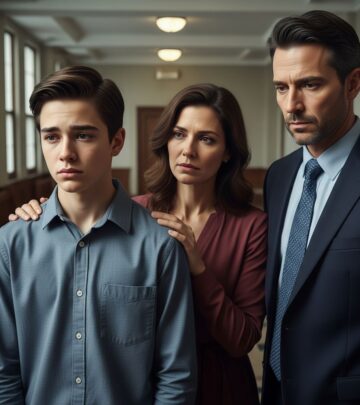

4. Child Protective Services and Loss of Custody

Criminal prosecution is only part of the picture. When a parent gives drugs to a child or engages in dangerous substance use, child protective services (CPS) or a similar agency may intervene to protect the child.

4.1. When Agencies Can Remove a Child

Under state child welfare laws, authorities can remove children from the home when the child is in immediate danger and there is no safe alternative. Substance-related danger can include:

- Evidence that a parent provided drugs to the child.

- Repeated overdoses or medical emergencies linked to household drug use.

- Active drug manufacturing in the home or vehicle.

- Parental intoxication that leaves young children unsupervised or exposes them to violence or unsafe environments.

Federal child welfare data show that substance use is a major driver of removals: in 2021, nearly 81,000 children were taken from their homes due to substance-use-related concerns.

4.2. Impact on Custody and Visitation

Even when CPS does not permanently remove a child, ongoing or serious substance misuse can affect family court decisions about custody and parenting time.

- Best interests of the child standard: Courts weigh a parent’s ability to provide a safe, stable environment. Substance use that endangers a child may lead to restricted or supervised visitation.

- Drug testing and monitoring: Judges may order random drug testing, treatment participation, or parenting programs as conditions of visitation or reunification.

- Potential termination of parental rights: In extreme or chronic cases where a parent does not address substance misuse, the state can seek to terminate parental rights.

5. Special Situations: Prenatal Exposure and Newborns

Some states treat prenatal drug exposure as a form of child abuse or neglect, triggering mandatory reporting and intervention at birth.

- Mandatory reporting: Federal law requires states to have procedures to notify child protective services when a newborn is affected by prenatal drug exposure, including withdrawal symptoms or fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

- Plans of safe care: Hospitals and agencies must create a plan to address the infant’s needs and support the family, which can include treatment referrals and supervision.

- Criminal and dependency implications: Depending on the state, maternal drug use during pregnancy can lead to child welfare proceedings and in some cases criminal charges, though approaches vary widely.

6. Role of Addiction and Access to Treatment

Many parents who give drugs to their children struggle with addiction themselves. In recent years, policy has increasingly focused on connecting families to treatment rather than relying solely on punishment.

- Substance use disorder as a health condition: Federal agencies such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) recognize substance use disorder as a chronic but treatable health condition, and promote family-centered treatment approaches.

- Special court programs: Some jurisdictions use family drug courts or similar programs that combine close monitoring with access to treatment and parenting support, aiming to preserve or restore safe family relationships where possible.

- Minors’ access to treatment: State laws often allow minors to consent to their own substance use treatment at certain ages, which can be important when a teen wants help even if a parent is struggling.

7. Defenses and Mitigating Factors in These Cases

Every case is fact-specific. While giving drugs to a child is inherently serious, the law still requires proof of particular elements, and there may be defenses or mitigating circumstances.

- Lack of knowledge or intent: In some charges, prosecutors must show the parent knowingly or intentionally exposed the child to drugs. Accidental exposure (for example, a toddler finding a hidden pill) may be charged differently than deliberate provision, though it can still lead to neglect allegations.

- Medical justification: If a child legitimately receives medication under a doctor’s orders, the parent’s role in administering the prescribed dosage is usually lawful. Problems arise when the parent deviates from medical instructions or shares their own medications without medical approval.

- Intervening in a child’s substance use: In rare situations, a parent might be accused of involvement when in fact they were trying to secure treatment or prevent harm—for example, bringing a teen’s drugs to the police or hospital. Legal advice is essential before taking such steps.

- Evidence of recovery: Even if the criminal case is strong, genuine participation in treatment, stable housing, and consistent negative drug tests can significantly influence outcomes in both criminal sentencing and family court.

Because laws differ by state and the stakes are high, anyone facing investigation or charges should speak with an experienced criminal defense and family law attorney in their jurisdiction.

8. Protecting Children and Seeking Help

Families caught in substance use crises need both legal guidance and practical support. Early action can reduce harm to children and sometimes avoid the most severe legal consequences.

8.1. What Concerned Parents or Relatives Can Do

- Contact a pediatrician or another trusted health professional to discuss the child’s potential exposure and needed medical care.

- Reach out to local addiction treatment providers or hotlines to find services for the parent and, if appropriate, for the child or teen.

- If the child is in immediate danger, contact emergency services or child protective authorities.

- Seek legal advice before making major decisions about custody, reporting, or guardianship.

8.2. National Resources

Federal and state agencies provide information and referrals for families dealing with substance use:

- SAMHSA behavioral health resources: Offers treatment locators, helplines, and educational materials on substance use and mental health.

- State child welfare agencies: Provide guidance on reporting suspected abuse or neglect and on support services for affected families.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Is it always a felony if a parent gives illegal drugs to a child?

In many states, intentionally giving a child illegal drugs is charged as a felony, especially when the substance is a controlled drug like methamphetamine, cocaine, or certain opioids. However, the exact charge and level (for example, lower-level felony versus higher-level felony) depend on state law, the child’s age, and whether the child was injured.

Q2: Can a parent lose custody just for using drugs, even if the child never used them?

Yes. Courts focus on whether the parent’s substance use threatens the child’s safety and well-being. A parent can lose custody or face restrictions on visitation if their substance use impairs supervision, exposes the child to violence or unsafe conditions, or leads to repeated crises, even if the child has not personally used the drugs.

Q3: What if a teenager wants substance use treatment but the parent refuses?

State laws increasingly allow minors to consent to certain forms of substance use treatment on their own, sometimes at a younger age than for mental health treatment. The exact age and type of services a minor can access without parental consent vary by jurisdiction, so teens and supportive adults should consult local laws or speak with a health provider familiar with state rules.

Q4: Are parents criminally liable if a child accidentally finds and takes their medication?

Liability depends on the circumstances and local law. Some cases are treated as tragic accidents, but if the medication was stored unsafely or the parent’s overall conduct is reckless, authorities may pursue charges for neglect or endangerment. Regardless of criminal charges, child protective services may investigate and impose safety requirements.

Q5: How can a parent with addiction problems reduce the risk of losing their children?

Steps such as entering evidence-based treatment, maintaining sobriety verified by testing, engaging with counseling or parenting services, and ensuring safe, stable housing can significantly influence how courts and agencies view a parent’s capacity to care for their children. Early voluntary treatment often leads to better legal and family outcomes than waiting until a crisis occurs.

References

- Parental Drug Use As Child Abuse — Intermountain Legal. 2023-06-01. https://intermountainlegal.net/criminal-defense/parental-drug-use-as-child-abuse/

- Substance Use and Child Custody — Texas Law Help. 2023-05-18. https://texaslawhelp.org/article/substance-use-and-child-custody

- Parental Addiction and Child Custody — American Addiction Centers. 2023-07-15. https://americanaddictioncenters.org/rehab-guide/family-members/custody

- What Can Parents Do? A Review of State Laws Regarding Decision Making for Adolescent Drug Abuse and Mental Health Treatment — Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2015-05-01. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4393016/

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) – About Us — U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2024-01-10. https://www.samhsa.gov

- New Crime of Exposing a Child to Controlled Substances and Other 2025 Drug Law Changes — UNC School of Government. 2025-07-31. https://nccriminallaw.sog.unc.edu/new-crime-of-exposing-a-child-to-controlled-substances-and-other-2025-drug-law-changes/

Read full bio of medha deb