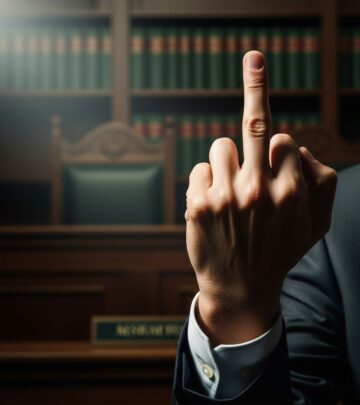

Flipping the Bird: Legal Boundaries of Expressive Gestures

Unpacking the First Amendment protections for offensive gestures like the middle finger—and where they meet their limits.

The middle finger gesture, often called ‘flipping the bird,’ stands as one of the most universally recognized symbols of defiance and disdain. While socially provocative, its legal standing in the United States hinges on robust First Amendment protections for expressive conduct. Courts have repeatedly affirmed that this vulgar gesture qualifies as speech, shielding it from government retaliation in most public contexts. However, boundaries exist, particularly in regulated environments like schools and courtrooms.

Understanding Expressive Conduct Under the First Amendment

The First Amendment safeguards not only spoken or written words but also symbolic actions that convey a specific message likely to be understood by viewers. The Supreme Court established this principle in Tinker v. Des Moines (1969), ruling that wearing armbands to protest the Vietnam War constituted protected expression. Extending this logic, federal courts have classified the middle finger as ‘expressive conduct’—a non-verbal communication of contempt or disagreement.

This protection stems from the amendment’s core purpose: preventing government censorship of offensive ideas. As courts note, free speech defenses are strongest when the expression repulses, ensuring ‘breathing space’ for democratic discourse. Yet, this right is not absolute; it yields to compelling interests like public safety or true threats.

Landmark Rulings: Middle Finger as Protected Speech Against Police

Police encounters represent the most litigated arena for this gesture. A pivotal case arose in 2017 when Michigan motorist Debra Cruise-Gulyas received leniency on a traffic stop but expressed dissatisfaction by extending her middle finger while driving away. Officer Matthew Minard responded by pulling her over again and issuing a full speeding ticket. The Sixth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled unanimously in Cruise-Gulyas v. Minard (2019) that this constituted First Amendment retaliation. Judge Jeffrey Sutton wrote that ‘any reasonable officer would know that a citizen who raises her middle finger engages in speech protected by the First Amendment,’ rejecting qualified immunity for the officer.

Similarly, in Indiana, Mark May flipped off State Trooper Matt Ames after perceiving reckless driving. Ames stopped May and cited him, prompting an ACLU lawsuit. The case underscored that such gestures, absent interference with duties or public endangerment, violate neither disorderly conduct nor obstruction laws. These decisions align with broader precedent: lower courts consistently hold that isolated middle finger displays to officers do not justify arrests.

| Case | Court | Key Holding | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cruise-Gulyas v. Minard | Sixth Circuit (2019) | Second stop retaliatory; gesture protected | Qualified immunity denied |

| May v. Ames (ACLU case) | Indiana Federal Court | Ticketing for gesture violates 1st/4th Amendments | Lawsuit filed; rights affirmed |

Historical Precedents and Broader Judicial Consensus

Courts beyond these incidents have long recognized the gesture’s legality. A comprehensive legal analysis traces convictions under breach-of-peace statutes, nearly all overturned on appeal, arguing they infringe First Amendment rights and squander judicial resources. The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that offensiveness alone cannot justify prohibition, as in Cohen v. California (1971), where ‘Fuck the Draft’ on a jacket was protected.

State and federal rulings echo this: Pennsylvania and Arkansas courts dismissed charges against individuals displaying the gesture publicly, deeming it free speech. Even symbolic cases, like a defendant gesturing at a judge, highlight limits only in contempt scenarios, not routine public use.

Exceptions Where Gestures Cross Legal Lines

- Fighting Words: If the gesture accompanies words inciting immediate violence, it loses protection under Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942). Mere vulgarity, however, does not qualify.

- True Threats: Gestures implying imminent harm, like paired with weapon brandishing, may trigger intervention.

- Obscenity: Rarely applicable; the gesture lacks the prurient interest required by Miller v. California (1973).

In traffic contexts, gesturing while endangering others (e.g., swerving) could invite charges, but the expression itself remains shielded.

Classroom and Courtroom Restrictions: Special Contexts

Public schools impose stricter rules under Tinker‘s ‘substantial disruption’ standard. Student gestures disrupting education have led to discipline, as courts prioritize learning environments. In courtrooms, contempt powers allow judges to penalize disruptive acts, such as a defendant gesturing mid-proceeding, potentially adding jail time.

Workplaces, especially government jobs, may regulate under employment policies, but private employers enjoy broader leeway absent contracts.

Public vs. Private Recipients: Who You Can Target

The gesture’s protection peaks against government actors like police, where state action triggers constitutional scrutiny. Private citizens face no First Amendment recourse; civil suits for assault require physical threat, not gestures alone. Road rage incidents illustrate risks: a German case involved a shooting over the gesture, though U.S. courts dismissed similar charges.

Prosecutorial analogies fail: unlike sentencing discretion, retaliatory traffic stops mimic revoking plea deals post-expression, deemed unconstitutional.

Practical Implications for Citizens and Officers

For individuals, the right empowers protest but invites practical backlash—escalated tensions or civil disputes. Officers must tolerate rudeness; training emphasizes de-escalation over retaliation. Qualified immunity shields only ‘clearly established’ violations; post-Cruise-Gulyas, middle finger cases meet this bar in many circuits.

Statistics from legal reviews show most prosecutions fail, reinforcing that pursuing charges erodes public trust and diverts resources.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is giving the middle finger to a police officer illegal?

No, it is protected expressive conduct under the First Amendment, as affirmed in multiple federal appeals courts. Retaliatory actions like unwarranted stops violate rights.

Can I be arrested for flipping off a teacher or judge?

In schools, yes, if it disrupts; in court, contempt charges are possible for direct defiance. Public streets offer stronger protection.

What if the gesture causes a fight?

If it qualifies as ‘fighting words’ provoking imminent violence, protection evaporates. Context matters.

Does this apply only to the middle finger?

Similar protections cover other vulgar gestures conveying protest or disdain, per expressive conduct doctrine.

Can private individuals sue over the gesture?

Not typically; it lacks elements of assault or battery without accompanying threats or actions.

Navigating Free Speech in a Polarized Society

As societal divides deepen, provocative expressions test constitutional limits. The middle finger embodies raw dissent, reminding us that free speech tolerates the vulgar to preserve the vital. Citizens wield this right responsibly, while authorities uphold it even amid personal affront. Ongoing cases will refine boundaries, but core precedent endures: rudeness is not criminality.

Legal scholars emphasize overprosecution’s costs: eroded rights, chilled expression, and inefficient justice. Policymakers should prioritize education on these rulings to prevent future disputes.

References

- Court Rules First Amendment Protects Motorist Who Gave the Middle Finger to Police Officer — Middle Tennessee State University First Amendment Encyclopedia. 2019-06-27. https://firstamendment.mtsu.edu/post/court-rules-first-amendment-protects-motorist-who-gave-the-middle-finger-to-police-officer/

- It’s Not Polite, But the Constitution Protects Your Right to Give the Finger to Police — ACLU of Indiana. 2020-01-15. https://www.aclu-in.org/news/its-not-polite-constitution-protects-your-right-give-finger-police/

- Middle Finger Archives — First Amendment Watch. 2019-12-12. https://firstamendmentwatch.org/tag/middle-finger/

- Digitus Impudicus: The Middle Finger and the Law — UC Davis Law Review, Prof. Margaret C. Jabobs (via PDF). 2008-01-01. https://lawreview.law.ucdavis.edu/sites/g/files/dgvnsk15026/files/media/documents/41-4_Robbins.pdf

- Can You Be Arrested for Giving the Finger to Police? — TalksOnLaw. 2023-05-10. https://www.talksonlaw.com/briefs/can-you-be-arrested-for-giving-the-finger-to-police

Read full bio of medha deb